Outside of London, Glasgow has one of the most intensive suburban railway networks in the UK, and just like their modern counterparts, rail workers in Glasgow in 1890 were fed up with working conditions and miniscule pay increases.

In those days, the majority of rail employees worked at one of three rival firms: the Caledonian, North British and Glasgow & South Western railway companies.

These companies were making huge profits as the number of Scots travelling by rail soared. At the same time working hours for rail staff was becoming intolerable. The average engine driver, signalman and shunter was working shifts of 14 to 15 hours a day. Some workers, it was found, were on shift for 20-30 hours at a stretch. In December 1890, Glasgow’s rail workers came together through their unions in what would become the largest rail strike ever witnessed in Scotland and demanded a 10-hour day.

Knowing their hand would be strengthened with Christmas fast approaching, the city’s rail workers realised it was now or never.

Picket lines were set up suddenly and without warning , on the morning of December 22, 1890. Workers in Edinburgh, Dundee and elsewhere joined the cause, sparking chaos across the country. On that first day, more than 4,500 workers abandoned their posts, with a further 5,000 joining them over the following four days. Passenger services immediately became late and irregular.

Trade was affected too, with goods traffic almost non-existent and factories across the Central Belt ceasing production due to a shortage of coal.

The tense situation reached a head at Motherwell on January 5, when the Caledonian Railway Company terminated the contracts of striking workers who had only recently taken up employment with the firm. The decision meant many young families being forcibly evicted from their homes, which had been supplied by the railway company.

Caledonian bosses said it was their legal entitlement to sack the workers – but this was an irrelevance to the men on strike and their supporters in North Lanarkshire.

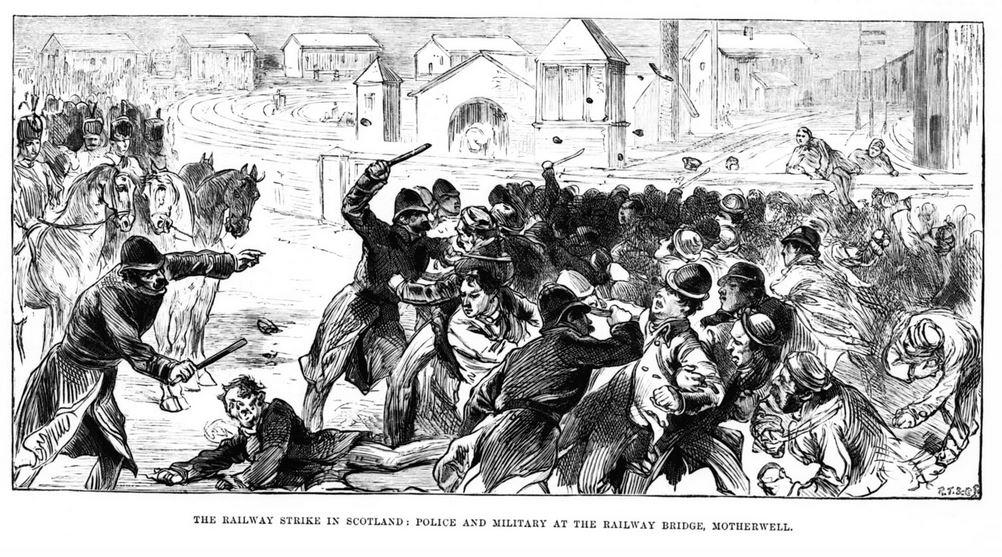

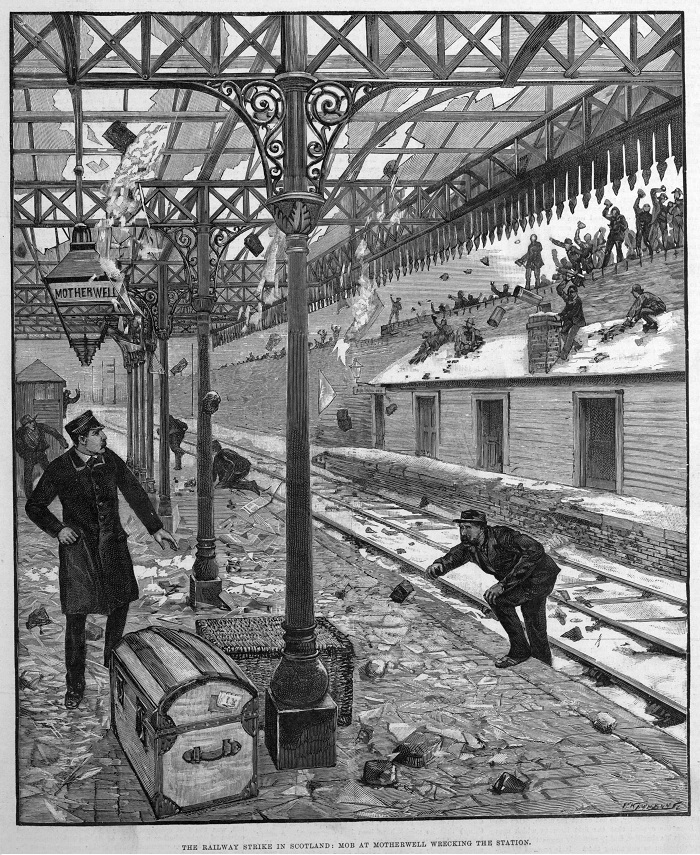

Incensed by the evictions, a hostile crowd of around 20,000 assembled to make their feelings clear. Riotous scenes erupted with protesters hurling rocks and causing damage to signal boxes on the railway lines. Mounted police and military were called upon to disperse the crowd, leaving a number of people injured.

After six long weeks the rail companies agreed to improve working hours for their staff and the strike ended.

The Caledonian Railway Company also dropped all actions for damages at Motherwell Station and allowed most of the men who had been fired to return to their company homes.

We can only hope that the current rail strike reaches a rapid and acceptable conclusion for all involved – not least of all, the commuter!